Tell Your Park Fire Story

YOUR STORY IS OUR HISTORY Cohasset Historical Society | Seth Mitchell | March 5, 2025 | Story collected by E. Vegvary and Karyl Clark | Written by E. Vegvary

It is July 2025, the anniversary month of the Park Fire. One year has passed since the devastating loss suffered by the mountain village of Cohasset.

Nestled on a dead-end volcanic ridge in the Sierra-Cascade foothills of Butte County, seventeen miles out of Chico, the community of Cohasset spreads east and west to canyons along the north-south running Cohasset Road for six miles before reaching the dirt Ponderosa Road. Ponderosa climbs and winds up into Tehama County, past Campbellville, to the helipad where it drops down into the Ishi Wilderness and Deer Creek.

Much of Cohasset and Campbellville were destroyed on the first and second day of the Park Fire, July 24 and 25, 2024. There is no official count of homes lost but most believe it to be around 250. With a 2020 census count of 427 homes, this loss of property has decimated the close-knit community.

Today, the previously quiet Cohasset Road has become a superhighway. Sierra Pacific Industries logging trucks begin their runs at 2 a.m. and end their day mid-afternoon. ROE dump trucks, tree cutting crews, and a veritable army of County inspectors travel the roads or work along the shoulders. Simultaneously, PGE is undergrounding lines because of another Butte County fire – the deadly 2018 Camp Fire in Paradise tragically set by faulty overhead PGE wires.

The hill is being clear cut, the burnt properties scraped clean of house foundations, debris, and toxic dirt. Last fall and winter, many residents were determined to let the burned trees stand. There was a deep need to allow the injured forest and wildlife time to heal, to breathe, to wait and see if any of the trees could still be alive. All that has become a bitter resignation as the spring revealed that the mixed conifer forest is clearly a near total loss. The big trees are dropped and cut into chunks for grinding. The smaller trees left standing, twisted and blackened. As the crews work patchwork through properties, the haphazard erasing of what’s left of a once riotously living forest is nearing completion.

Residents no longer recognize their beloved mountain or their properties. There is a question of how many of those who were burned out will return to rebuild their lives here. Politics and financial feasibility seem to go hand in hand when it comes to people being able to rebuild. The community feels like a body in shock. The collective identity of protective ownership of the ridge is just another loss to residents’ sense of home.

The Park Fire became the largest wildland fire of California's 2024 wildfire season and the fourth largest in California history. It burned out of the valley, through Cohasset, throughout Sierra Pacific Industries timberlands, into Tehama County past Campbellville, down into the true wilds of the Ishi Wilderness, destroying the bridge built by the CCC in the 1930’s to cross Deer Creek, through the Deer Creek Campground, and past Black Rock where Ishi’s brain is rumored to have been buried, and kept on burning into Shasta County.

The Park Fire’s destruction of everything held dear by Cohasset residents was catastrophic.

But there are seven hundred acres at the heart of Cohasset that did not burn. How such a thing could happen is still a mystery to many.

Not to Seth Mitchell. He was there. He helped save it.

It took over six months’ time for Seth to be able to sit down and tell his story for the Tell Your Park Fire Story project. He has been busy! The forty-four-year-old is a certified arborist and forest administrator. For half a year, he has been out in the burn scar almost daily assessing damaged trees and felling hundreds of hazardous trees. He has been generous with his skills and knowledge, working closely with the Cohasset Community Association as a volunteer and member of the Emergency Preparedness Committee.

But like so many other survivors, Seth has also been working through the experience of the fire. In his case, grappling with the residual trauma incurred from making the defiant decision to remain in Cohasset and protect what he could during the first week of the Park Fire.

The grieving process continues and for those who lost everything, springtime was particularly difficult. Daffodils and paperwhites blooming in burnt out homesteads, the black oaks struggling to leaf out. The summer has been even more dreadful. A landscape once familiar changes daily, strange, and deeply depressing.

But in the Green Island, the deciduous trees have woken up and ravens squawk, songbirds sing, and squirrels chitter. This forested haven is also filling with wildlife refuges. Bear, bats, deer, fishers. Of course, it is only the larger mammals or winged creatures that have been able to relocate. The overwhelming decimation of insects, reptiles, rodents, and small mammals are rarely mentioned when discussing wildland fire’s deadly toll.

Some in the Green Island feel what can only be referred to as “survivor’s guilt” even though they did not cause the destruction of Cohasset. The 717 unburned acres at the heart of the community are a miracle and those living in it count it as such and feel a complicated gratefulness. Those who lost their properties feel a complicated combination of sadness and gratitude. Many have stated that the Green Island helps them to remember what Cohasset was and what it will be again someday. But survivors of the fire understand that it will be a lifetime or more before their property resembles what it once was.

Seth Mitchell’s home is in the Green Island. He grows emotional at any discussion of those properties that did not survive. It’s a constant ache and regret for him. Seth defied all orders to evacuate so that he could stay and fight the fire with a handful of others. His plan was never to remain only on his property but to use every tool at his disposal to save as many residents, animals, homes, and properties as a single body could possibly save during the chaos and terror of the wildfire.

On Wednesday, July 24, 2024, the Park Fire was set just before 3:00 in the afternoon in Upper Bidwell Park in Chico. Although the park is over twenty miles away, within thirty minutes Cohasset was under evacuation warnings. Most residents began to pack and leave. By 5:30 Sheriff Kory Honea made the life-saving decision to upgrade the warnings to orders. Residents continued to evacuate. Those who stayed the first night were forced out of their homes the second day as the fire burned up and out of both east and west flanking canyons, roaring into Cohasset like a freight train ablaze. You would be hard pressed to find a survivor who regrets their decision to follow evacuation orders.

No property is worth a life, yet how many properties can be saved by owners who have fire knowledge? Can homeowners save their homes and the homes of their neighbors with the help of professionally trained personnel augmented by their own layperson education? Cal Fire and Rescue and the Sheriff’s Department will not, cannot, be flexible in any way regarding homeowners choosing to stay during a wildfire to protect their belongings. "Stay safe, never hesitate to evacuate!" "Don’t delay, get away today!"

In Cohasset, no one should have rationally attempted to survive the furnace that incinerated the eastern side of Cohasset Road. On the west side, on the north end and on the south end, a handful of residents made the decision to stay and fight. On the east side, a few men returned to their properties undercover to guard against spot fires. All these people were able to protect their homes. None of them did it without preparation, professional hands-on advice, assistance, or training.

It is a misdemeanor to remain in or return to an evacuated area. Additionally, residents who refuse to evacuate may be grimly tolerated but can be removed by force if they leave their own property.

Seth is aware of the legal risk of defying evacuation orders. He is also trained to fight fires and protect life and property from fire. He has spent his life in the forests of Northern California and all his professional life working in the mountains and foothills as a forest administrator and fishing guide. Additionally, he’s a long-time member of the Cohasset Community Association’s Emergency Preparedness Committee, the neighborhood Bucket Brigade, and has assisted with various forestry projects through the remote hills of Northern California. His decision to remain was an educated one.

During the week he was “on the hill” working tirelessly day and night, shoulder to shoulder with a handful of others who stayed, some in a professional capacity and some not, he saw things that to this day he is unable to describe without deep turmoil and harrowing emotion - firenadoes, a smoke column rising above Campbellville that would have acted like an atomic bomb if it collapsed, injured and dying wildlife, and the staggering number of homes burning. Amidst these traumatic experiences, however, he made a difference that isn’t truly understood by many. His indefatigable work helped to save the Green Island and a few properties outside its perimeters.

The day of the fire, Seth’s focus was his family’s safety. No one could have predicted that afternoon the terrible outcome for Cohasset. Seth is one of those who have said they had a feeling about that day and that fire. An instinct. He also knew without question that he would be putting himself on the front line.

Fighting wildland fire requires a tactical approach. Especially after the initial onslaught has passed. Homes that survive that first wall of flame can be lost a day or even several days later due to spot fires and smoldering embers. This is where the boots on the ground made the difference for the Green Island. Seth’s boots.

Seth, Cohasset Volunteer Company Captain Jonathan Tehan, two other Cohasset Volunteer Firefighters and a small group of neighbors began the deliberate work that needed to be done. Seth and Jonathan were already friends. They formed a formidable team. But there were neighbors with whom Seth readily admits he was less than friendly pre-fire. Now, post-fire - brothers for life he says, and he means it.

Luck favors the prepared, goes the saying. Seth was prepared and had readied himself to be prepared for years. Under the wise counsel of retired CHP dispatcher Maggie Krehbiel, chairperson of the Emergency Preparedness Committee, Seth brought his knowledge of handheld radios, portable water, and tree falling to those interested in prepping for the inevitable. Additionally, in 2020 Maggie founded the less formal Bucket Brigade and Seth quickly became an integral member of that group as well. During Snowmaggedon, Seth and another Bucket Brigadier worked tirelessly to aid upper Cohasset. They cleared downed trees, brought supplies into snowbound residents, helped with rooftop snow removal, and kept the community updated via the handheld radios throughout the power outage.

It was no different during the Park Fire.

Seth’s story is lengthy and detailed. He kept a fascinating record of his experience during the fire. Logs, photographs, timestamps, maps. Testimonials to his dedication and devotion to Cohasset, Cohassians, and the forest. He hopes to someday be able to document all of this in book form. We can highlight some of his experiences.

There were very few local firefighters deployed in Cohasset. Cohasset’s own Cal Fire Station personnel were dispatched off the hill to Upper Bidwell Park. The Cohasset Volunteer Company crewed Station #22 in their absence. The Volunteers assigned themselves several important jobs to ensure that out of town crews on the mountain would be able to work at optimum levels. They installed the reflective street address signs, slated to be delivered at the annual Bazaar held in August. Jonathan wrote in street addresses on maps he photocopied to hand out at daily briefings.

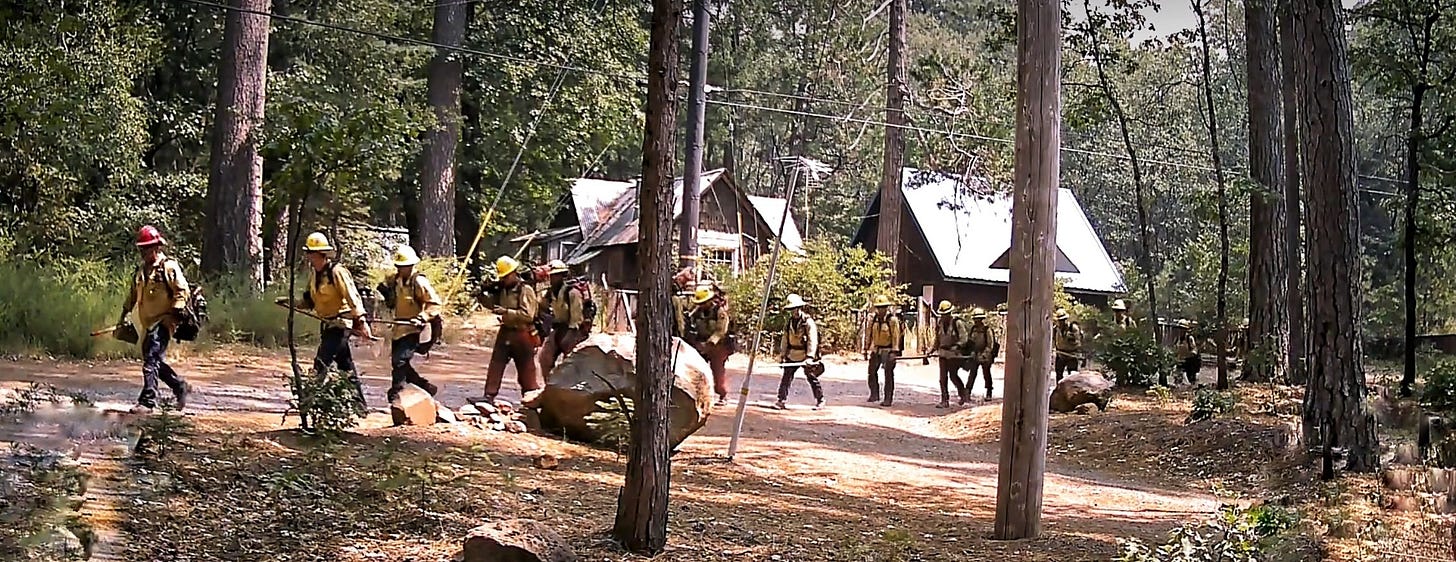

The volunteers and those Cohassians working with them, began to spend their nights out on the roads, searching for hot spots and spot fires, candling trees, and smoldering stumps. They then circled these spots on the morning brief maps, handing them out to the engines working in Cohasset. Spot fires are easier to see in the dark and the small band of local men worked tirelessly in trucks and on quads to map these dangerous fires.

There are stories of trees on fire being dropped, trees being dropped before they could ignite and combust groves. There are stories of backfires being lit because all firefighters know that things “in the black” won’t burn.

Water became a significant issue. Seth knew that the massive holding tank at the closed elementary school grounds had been neglected and rendered inoperable. He focused on the 6,000-gallon tank at the Cohasset Community Association grounds. Without power, a generator had to be brought online to utilize the tank. The CCA’s generator, purchased with PGE grant monies, was being used to power the building. Maggie offered the use of a generator she and her husband, Bob, had stored on their back deck and Seth retrieved it, stopping to water and feed Maggie’s chickens. Maintaining and accessing the CCA water tank is now at the top of Seth’s list for future preparedness.

Many residents relayed through Maggie the location of gas cans, quads, portable water, and freezers full of meat for the use of those who were on the hill. Seth and his crew had what they needed thanks to the preparedness of others.

Seth also opened and staffed the Cohasset Community Association building. It was always the intention to use the building in an emergency, and once opened it served its purpose, quickly becoming one of the most reliable safe spaces on the hill. The men used it to triage, to touch base with one another and with the firefighters, and to sleep. It was the drop off point for supplies that Seth relayed to Maggie via GMRS.

Most importantly, he and others used it during blow-ups to shelter in place, specifically the night they were forced to retreat from the western canyon edge; the night Seth Mitchell momentarily lost all hope as the fire exploded up and out of Rock Creek canyon.

Throughout those horrifying hours, Seth could speak with Maggie on the radio. He had a lifeline. Maggie had become a dispatcher for the soul, if you will.

Despite the access Seth had created with the CCA’s water supply; water continued to be an issue. He and Jonathan drove up past the end of the paved road to the Cold Spring and sure enough it was full of spring water. They began to direct pumpers to this source and they themselves filled portable water trailers there. Unlike the numerous locked gates throughout Southern Pacific Industries timberlands, the SPI gate leading to the Cold Spring was unlocked because long-term Cohasset family, the Apels had fought for a decades-owned easement to these headwaters of Rock Creek and had won.

There was no rest during that week. The first order of each day was to find and put out spot fires. The protective circle Seth drew around the Green Island on an evacuation map for Cohasset was a fire line he was determined to help hold. Early on, Cal Fire launched an aggressive aerial firefight along the Rock Creek canyon edge to keep flames from running uphill and into the western flank of Cohasset. Hand crews worked diligently along this line. On the east side of Cohasset Road, boots on the ground were fighting spot fires at Maple Creek Ranch. Seth and the Volunteer Company were instrumental in helping to defend the entirety of the western side of the still green zone.

For months after the fire there were two large-diameter extinguished spot fires that could be seen near and on Calochortus Way. One had burned next to the ATT hub on Cohasset Road and the other behind a home. Both stark reminders of how vital Seth’s work was to the Green Island as he searched for ember-sparked fires, began to douse them, and called in to Cal Fire for backup.

Seth also patrolled regularly outside the green zone for properties that might be saved by his ability to fell trees. More than one family credit Seth with saving their homes.

When he wasn’t dropping trees, and dousing spot fires, he was busy setting up game cams on the main roads to monitor who was coming and going. He and his crew patrolled throughout the day and night for looters.

The first two days he also searched for any residents who might have gotten stranded. As he and Maggie settled into the rhythm of their hill-to-valley radio connection, he began to be able to respond to requests from evacuees. He checked on pets, feeding and watering them. In the process, he fed and watered wildlife, too.

On the third and fourth days, he was able to certify proof of life to those whose properties were still standing. Traumatically, at the same time, he and the crew began the terrible job of breaking dreadful news. Gently, compassionately but factually informing friends and neighbors that their homes were gone, reluctantly sending cell photos.

In the early morning hours of July 3oth, six days after the fire began, Seth was stopped by neighboring County deputies during his nightly hot spot and looter patrol. He was forcibly taken out of Cohasset.

He was simultaneously triumphant and defeated. And he was exhausted beyond words. When all you have left to give is blood and tears, then you have given everything.

He would return with the community when the evacuation orders were downgraded to warnings which allowed residents whose homes survived to return. The resultant overwhelming shock and grief his community faced, would envelop him entirely for the next few months.

Seth would be the first one to admit that he will be paying the toll of the Park Fire for the rest of his life. He sees the cost every day when he wakes in the Green Island but ventures out to work in the burn scar. He knows better than anyone else on the hill that he was one of those who helped win the battle, but that the war was lost.

We are such a fortunate community to have you, Seth.

This is excellent.

What a hero Seth Mitchell is!